It's the title of a 2006 documentary film about a woman named Teri Horton, a 73-year old former long-haul truck driver, who bought a thrift shop painting for $5 for her friend in 1992. She bought it as a joke because it was ugly, but she had to take it back when it didn't fit in her friend's trailer. So she brought it home and tried to earn her money back, attempting to sell it at a yard sale. There a local art teacher informed her it may be a Jackson Pollock. Guess what she said next?

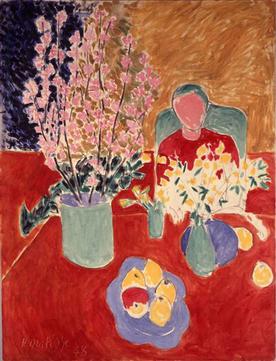

For almost 20 years she has been searching for answers. And the answers are shrouded in intrigue. Initial responses from the art world dismissed her painting as "pretty, superficial, and frivolous." One of her loudest critics has been Thomas Hoving, a former curator and director of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's no Pollock says Hoving, because "It has no Pollock soul or heart."

In his own words, Hoving describes why he thinks the painting is NOT a Pollock:

* It is too neat and too sweet, using soigné colors that Pollock never used.

* Some lines are perfectly straight. It’s hard to drip straight lines.

* The canvas is commercially sized, which means that paint does not come through the back of the canvas. All real Pollocks are unsized and his paint patterns can easily be seen from the back.

* The thing is painted with acrylics. Pollock never used acrylics.

"I figured that the $5 picture was not a fake, but a decorator’s piece. You know, 'Gimme some big abstract -- like Pollock -- but make it with the colors of my new living room.' There are dozens around."

So the art world said no to her and she turned to science. Horton hired a respected, Canadian forensic scientist, Peter Paul Biro, to scientifically authenticate the painting. What he found was compelling: a fingerprint on the back of the canvas matches a fingerprint on a paint can in Pollock's studio. (The studio is preserved as a museum.)

|

| The fingerprint on Pollock's paint can. |

Game over. It's a Pollock. $50 million dollars please.

Not so fast.

With her evidence in hand, Horton applied to the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) to officially have the painting attributed to Pollock. IFAR said it was a fake. The painting is "too obsessively finespun," and the colors "too coyly, too consciously chosen." As for the fingerprints, the report states "Biro's methods of analyzing fingerprints have not been universally accepted." He used somewhere between 6 and 19 points to positively identify the prints, but "some experts in the forensic field believe that those numbers are too low. Interpol, for example, uses a minimum of 12 points."

Sylvia Hochfield then wrote an editorial in June 2008 for ARTnews claiming that both the print on the paint can and its matching print on the attributed Pollock are forgeries. The prints were reexamined by Pat Wertheim, a criminalist in the Arizona Department of Public Safety and an expert on fingerprint forgery and fabrication detection. Biro reacted strongly to Wertheim’s report, accusing him, in an e-mail to ARTnews, of “supercilious interfering” and calling his work “suspect.” Wertheim responded, “My report is scientifically verifiable.”

So is it real? Some experts say yes. Other experts say no. A friend of Pollock isn't sure.

Here is an interview with Teri Horton herself, talking to Anderson Cooper about her painting:

And here is the other side. Thomas Hoving's article in full: The Fate of the $5 Pollock as well as Hochfield's editorial The Blue Print.

Whose side are you on? Is this controversy about proving the authenticity of the piece? Or is this a story about the challenges faced by an average citizen taking on the elitist, high-stakes art world? If this painting had been found in a loft in New York City would the story be different? Can science prove something meaningful while "experts" say it's not? If science someday does authenticate it for sure, how will people react to the piece?

Teri Horton gets the last word today. She told the New York times in 2006, that she remained confident she, and her painting, would be vindicated. Despite the lack of confirmed attribution, Horton has been offered several single-digit million dollar prices for her painting, which she constantly turns down on principle. She maintains that she she will sell her painting at her price — no less than $50 million — within her lifetime. And if that does not happen?

“Before I let them take advantage of me,” she said, smiling broadly, “I’ll burn that son of a bitch.”